CUMBERLAND PHYSIOTHERAPY PARRAMATTA:Tendons are found all over the body and while you may know a little about them, you might be surprised to learn a few of these facts.

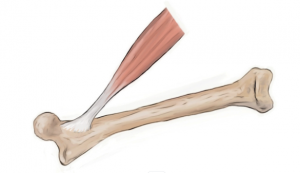

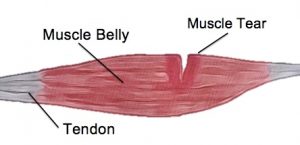

1. Tendons can be found at the ends of muscles. Tendons are simply connective tissues that attach muscles to bone and help them move our joints when they contract.

2. Tendons come in many shapes and sizes. While the most recognisable shape is the long thin kind (such as the Achilles tendon), they can also be flat and thin or very thick, depending on the shape of the muscle and attachment of the bone. A thin flat tendon is also known by the name aponeurosis.

3. Tendons are able to act like elastic bands, they can stretch and bounce back into shape. Like elastic bands, if too much force is applied they can stretch or tear.

4. Unlike elastic bands, tendons are living tissue and their properties are affected by many different factors. Seemingly unrelated things such as hormonal changes, autoimmune disorders and nutrition can all affect a tendon’s ability to withstand load.

5. Tendons don’t only attach muscles to bone, they can attach to other structures as well such as the eyeball.

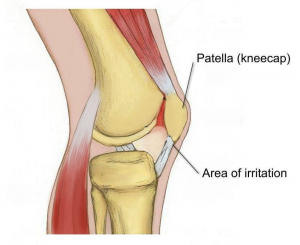

6. Tendons can tear however; more often they are injured through overuse. Healing of tendons can be quite slow as they have less blood supply than other tissues of the body, such as muscles.

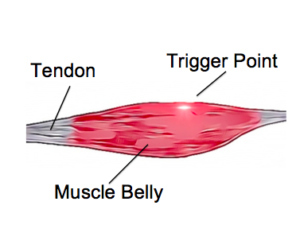

7. Tendons are mostly made of organised collagen fibres. Areas of tendon degeneration have been shown to have collagen fibres that are disorganised, with this area having less strength and elasticity.

8.The Achilles tendon is the strongest tendon in the body. This connects the large calf muscles to the back of the heel to point the ankle away from the body. Most tendons are simply named for the muscle they attach to, however the Achilles has it’s own name, named for the mythical Greek character who’s heel was his only point of weakness.

9. The smallest tendon is located in the inner ear, attaching to the smallest muscle in the body.

10. Tendons and muscles work together to move your joints and are called a contractile unit.